1987 · PG · 2h 8min

Drama · Fantasy · Romance · Foreign Language

Original title Der Himmel über Berlin

Director Wim Wenders

Stars Bruno Ganz · Solveig Dommartin · Otto Sander · Curt Bois · Peter Falk

Written by Wim Wenders · Peter Handke · Richard Reitinger

Music Jürgen Knieper · Laurent Petitgand

Countries of origin West Germany · France

Language(s) Spoken German · English · French · Turkish · Hebrew · Spanish · Japanese

Sound Mix Dolby Stereo Colour Colour, Black & White Aspect Ratio 1.66 : 1

Budget 5 million DM Box office USD$3.2 million

An angel tires of his purely ethereal life of merely overseeing the human activity of Berlin's residents and longs for the tangible joys of physical existence when he falls in love with a mortal.

Heavy.

"A beautiful, literate and romantic piece of cinema."

—Ian Nathan, Empire Magazine

Plot

In a Berlin divided by the Berlin Wall, two angels, Damiel and Cassiel, watch the city, unseen and unheard by its human inhabitants. They observe and listen to the thoughts of Berliners, including a pregnant woman in an ambulance on the way to the hospital, a young prostitute standing by a busy road, and a broken man who feels betrayed by his wife. Their raison d'être is, as Cassiel says, to "assemble, testify, preserve" reality. Damiel and Cassiel have always existed as angels; they were in Berlin before it was a city, and before there were any humans.

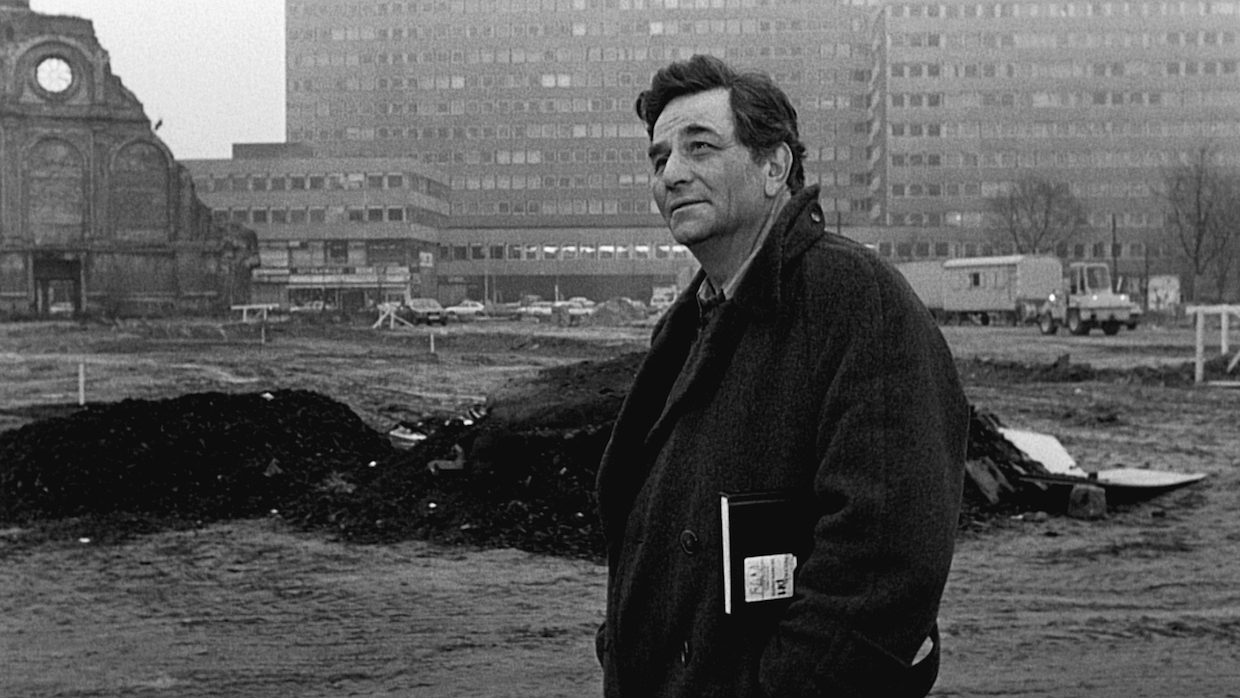

Among the Berliners they encounter in their wanderings is an old man named Homer, who dreams of an "epic of peace". Cassiel follows the old man as he looks for the then-demolished Potsdamer Platz in an open field, and finds only the graffiti-covered Wall. Although Damiel and Cassiel are pure observers, visible only to children, and incapable of any interaction with the physical world, Damiel begins to fall in love with a profoundly lonely circus trapeze artist named Marion. She lives by herself in a caravan in West Berlin, until she receives the news that her group, the Circus Alekan, will be closing down. Depressed, she dances alone to the music of Crime & the City Solution, and drifts through the city.

Meanwhile, actor Peter Falk arrives in West Berlin to make a film about the city's Nazi past. Falk was once an angel, who, having grown tired of always observing and never experiencing, renounced his immortality to become a participant in the world. Also growing weary of infinity, Damiel's longing is for the genuineness and limits of human existence. He meets Marion in a dream, and is surprised when Falk senses his presence and tells him about the pleasures of human life.

Damiel is finally persuaded to shed his immortality. He experiences life for the first time: he bleeds, sees colours, tastes food and drinks coffee. Meanwhile, Cassiel taps into the mind of a young man just about to commit suicide by jumping off a building. Cassiel tries to save the young man but is unable to do so, and is left tormented by the experience. Sensing Cassiel's presence, Falk reaches out to him as he had Damiel, but Cassiel is unwilling to follow their example. Eventually, Damiel meets the trapeze artist Marion at a bar during a concert by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and she greets him and speaks about finally finding a love that is serious and can make her feel complete. The next day, Damiel considers how his time with Marion taught him to feel amazed, and how he has gained knowledge no angel is capable of achieving.

"Wings of Desire is one of Wenders's most stunning achievements."

—Jonathon Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader

Themes & Interpretation

The concept of angels, spirits or ghosts who help humans on Earth had been common in cinema, from Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941) to the 1946 works It's a Wonderful Life and A Matter of Life and Death. Many earlier U.S. and U.K. films demonstrate high amounts of reverence, while others allow reasonable amounts of fun. Powell and Pressburger's A Matter of Life and Death presents an early example of spirits being jealous of the lives of humans. The shift from monochrome to colour, to distinguish the angels' reality from that of the mortals, was also used in Powell and Pressburger's film. While Wings of Desire does not portray Berliners as living in a utopia, academic Roger Cook wrote that the fact that people have pleasure "gives, as the English title suggests, wings to desire".

God is not mentioned in the film, and is only referred to in the sequel Faraway, So Close! when the angels state a purpose to connect humans with "Him". Scholars Robert Phillip Kolker and Peter Beickene attributed the apparent lack of God to New Age beliefs, remarking Damiel's "fall" is similar to the story of Lucifer, though not related to evil. Reviewer Jeffrey Overstreet concurred that "Wenders had left his church upbringing behind", and the cinematic angels are "inventions he could craft to his specifications", with little regard for biblical beliefs. Overstreet characterized them as "whimsical metaphors, characters who have lost the joy of sensual human experience". Nevertheless, Professor Craig Detweiler believed the sky-level view of Berlin and the idea of guardian angels evoke God. Authors Martin Brady and Joanne Leal added that even if Damiel is tempted by seemingly profane things, the atmosphere of Berlin means the human Damiel is still in "a place of poetry, myth and religion".

In one scene, Damiel and Cassiel meet to share stories in their observations, with their function revealed to be one of preserving the past. Professor Alexander Graf wrote this connects them to cinema, with Wenders noting Wings of Desire itself depicts or shows places in Berlin that have since been destroyed or altered, including a bridge, Potsdamer Platz and the Wall.

The closing titles state: "Dedicated to all the former angels, but especially to Yasujiro, François and Andrej" (all references to Wenders' fellow filmmakers Yasujirō Ozu, François Truffaut, and Andrei Tarkovsky). These directors had all died before the release of the film, with Kolker and Beickene arguing they were an influence on Wenders: Ozu had taught Wenders order; Truffaut the observation of people, especially youth; and Tarkovsky, a less clear influence on Wenders, consideration of morality and beauty. Identifying directors as angels could tie in with the film characters' function to record.

Academic Laura Marcus believed a connection between cinema and print is also established in the angels' affinity for libraries, as Wenders portrays the library as a tool of "memory, and public space", making it a miraculous place. The depiction of Damiel, by using a pen or an immaterial pen, to write Song of Childhood, is also tribute to print and literacy, introducing, or as Marcus hypothesized, "perhaps even releasing, the visual images that follow". Kolker and Beickene interpreted the use of poetry as part of screenwriter Peter Handke's efforts to elevate language above common rhetoric to the spiritual. Reviewing the poetry, Detweiler remarked that Handke's Song of Childhood bears parallels to St. Paul's 1 Corinthians 13 ("When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child ... "). Professor Terrie Waddell added that the poem established "centrality of childhood" as a key theme, noting that the children can see angels and accept them without question, tying them in with the phenomenon of imaginary friends.

The film has also been read as a call for German reunification, which followed in 1990. Essayists David Caldwell and Paul Rea saw it as presenting a series of two opposites: East and West, angel and human, male and female. Wenders' angels are not bound by the Wall, reflecting East and West Berlin's shared space, though East Berlin remains primarily black and white. Scholar Martin Jesinghausen believed the film presumed reunification would never happen, and contemplated its statements on divides, including territorial and "higher" divides, "physicality and spirituality, art and reality, black and white and colour".

Researcher Helen Stoddart, in discussing the depiction of the circus and trapeze artist Marion in particular, submitted that Marion is the classic circus character, creating an image of danger and then potential. Stoddart argued that Homer and Marion may find the future in what remains of history found in Berlin. Stoddart considered the circular nature of the story, including a parallel between the angel who cannot see the physical (Damiel), and the faux angel (Marion) who can "see the faces". Marion also observes that all directions lead to the Wall, and the final French dialogue "We have embarked" while the screen states "To be continued", suggests "final movement to a new beginning".

Writing in the journal Film and Philosophy, Nathan Wolfson cites Roland Barthes's work—especially S/Z—as a model to argue that "This 'angelic' portion of Wings of Desire deliberately invokes in the viewer a set of specific responses. These responses provide the foundation for the transformation that Damiel and Marion participate in. The film prepares the viewer for an analogous transformation, and invites the viewer to participate in this process, through an exploration of authorship and agency."

"A sublimely beautiful, deeply romantic film for our times."

—David Stratton, Variety